Ranked Second in the Nation for OD’s, Ohio Is Now Making Great Strides

In March of 2017, a 28-year-old Middletown, Ohio, man was found slumped over his steering wheel, unconscious from an opioid overdose.

It took six units of Narcan — three times the typical dosage — for the local police to revive him.

Later that same year, a Dayton police officer made headlines when he stated that his department had revived another opioid addict 20 times with Narcan.

Ohio: The State of Addiction

These two scenarios exemplify Ohio’s dire state of affairs with regard to its drug problem. In 2017, opioid overdose was a way of life (and a way of death) in the Buckeye State. In Montgomery County, the coroner’s office had to rent refrigerated trailers just to keep the bodies from piling up.

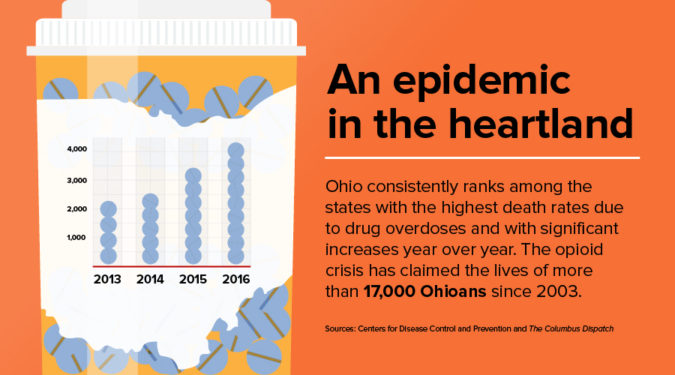

Ohio had 4,854 accidental drug overdose deaths in 2017 — an increase of more than 800 over the previous year. It ranked second in the nation for overall drug-related deaths, after its neighboring state of West Virginia. (Nationwide, drug overdose deaths were so high, they reduced the average U.S. life expectancy.)

While it may have peaked in 2017, Ohio’s overdose death rate had been climbing steadily for several years:

Dramatic Turn of Events

Then, in 2018, those figures began to plunge in several metropolitan areas across the state.

In Dayton, the 2018 overdose rate declined by 54 percent. In Hamilton County, which includes Cincinnati, overdose deaths dropped 31 percent. By September of 2018, the Ohio Department of Health released a report showing that prescription opioid-related overdose deaths had reached an eight-year low, while heroin-related deaths were at a four-year low.

In October 2018, an editorial in the Youngstown Vindicator stated that “drug-abuse deaths in Ohio declined by about 25 percent” in the first half of 2018.

“They just began to abruptly drop off,” said Dayton physician Dr. Randy Marriott. State officials point to several factors for the sharp decline in mortality rates.

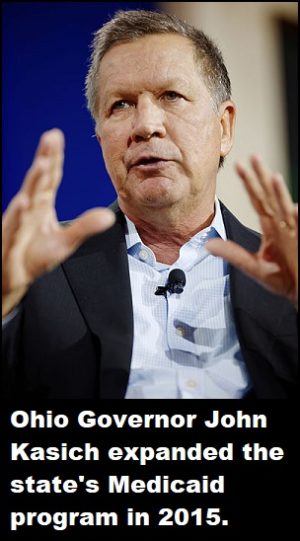

Expanding Medicaid in Ohio

But if you ask Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley, nothing has had as big an impact on overdose deaths as former Gov. John Kasich’s decision to expand Medicaid in 2015. That move gave nearly 700,000 low-income adults access to free addiction and mental health treatment.

But if you ask Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley, nothing has had as big an impact on overdose deaths as former Gov. John Kasich’s decision to expand Medicaid in 2015. That move gave nearly 700,000 low-income adults access to free addiction and mental health treatment.

And it resulted in dozens of new residential and outpatient treatment providers. These providers dispense methadone, buprenorphine and naltrexone, the three medications approved by the F.D.A. to treat opioid addiction. (See related article, “How Effective Is Methadone Treatment?“)

“It’s the basis — the basis — for everything we’ve built regarding treatment,” Mayor Whaley said in an interview at City Hall. “If you’re a state that does not have Medicaid expansion, you can’t build a system for addressing this disease.”

“If you’re a state that does not have Medicaid expansion, you can’t build a system for addressing this disease.”

According to Gov. Kasich, the state is spending $1 billion a year to address the opioid epidemic, and a big chunk of that is Medicaid funds. Addiction treatment is now available for nearly all low-income residents who need it.

It’s only fitting that Medicaid should pay for these residents’ treatment, since they are the people most vulnerable to opioid abuse in the first place. According to a 2018 Health and Human Services report, “Medicaid beneficiaries … are more likely than non-beneficiaries to have chronic conditions and comorbidities [when two or more diseases occur at the same time in a single patient] that require pain relief, especially those who qualify because of a disability.”

Carfentanil Fading

Another major change, at least in the Dayton area, is the fading presence of carfentanil — a synthetic opioid 100 times more potent than fentanyl. From July 2016 through June 2017, Ohio experienced 1,106 carfentanil-related deaths.

It was showing up regularly in just about every street drug, including methamphetamine, cocaine and fentanyl. No one knew why Ohio saw more carfentanil than anywhere else, but it played a huge role in the explosion of deaths in 2017.

Then it started to dwindle. Perhaps because dealers were killing off their customer base.

— Article continues below —

Prevalence of Naloxone

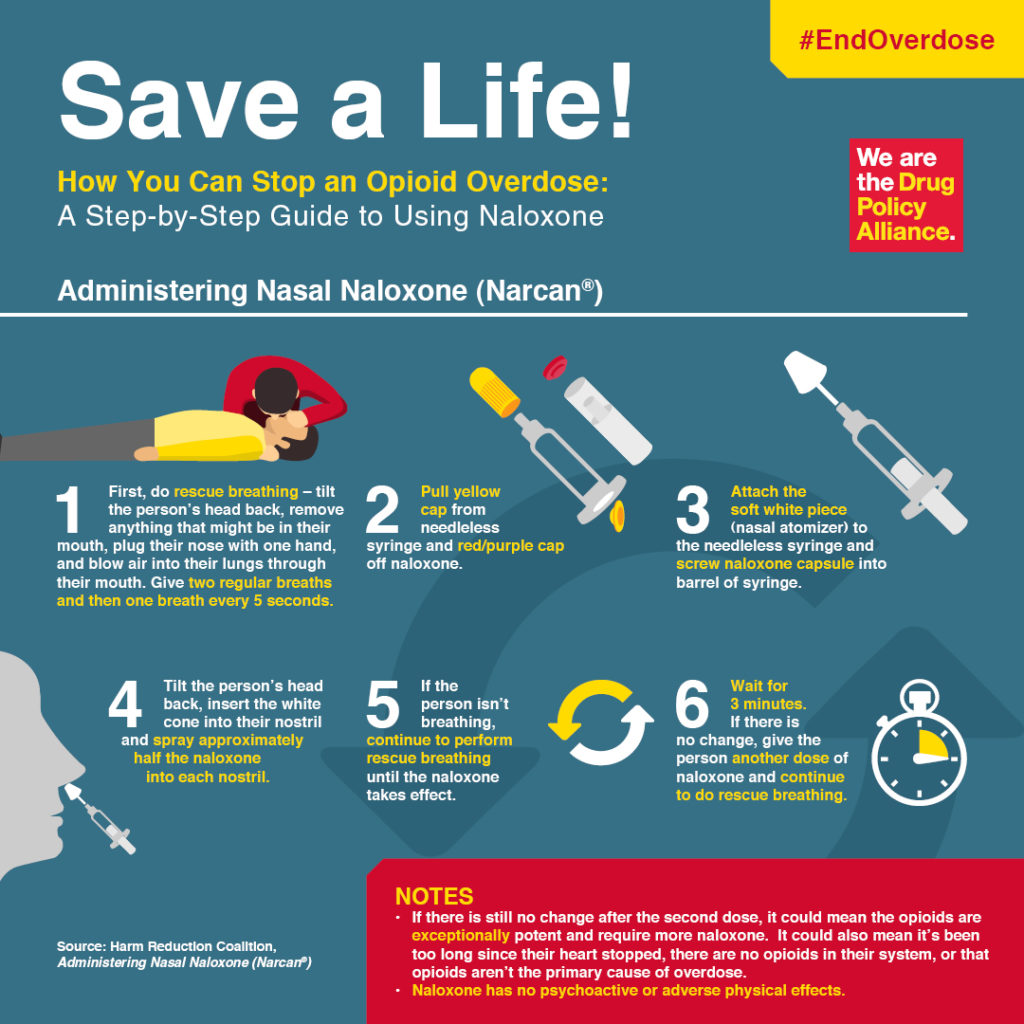

There’s also been a big push for wider availability of the overdose reversal drug naloxone.

As part of Ohio’s statewide initiative Project DAWN (Deaths Avoided With Naloxone), most counties now offer it for free. Commonly known by its brand name of Narcan, naloxone revives the victim within seconds.

As part of Ohio’s statewide initiative Project DAWN (Deaths Avoided With Naloxone), most counties now offer it for free. Commonly known by its brand name of Narcan, naloxone revives the victim within seconds.

Beginning in 2014, Dayton Police Chief Richard Biehl directed all his officers to carry Narcan. “We really jumped on it because we saw it as absolutely consistent with our public mission to save lives,” Chief Biehl said.

In fact, a recent Stanford University study indicates that wide availability of naloxone could prevent more overdose deaths than any other approach.

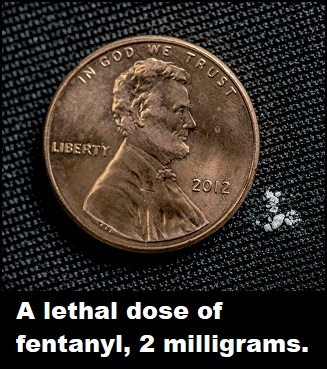

But the demand for higher doses of Narcan are increasing. In 2017, nearly 75 percent of Ohio’s overdose deaths involved the highly lethal drug fentanyl. Victims of fentanyl overdose are much harder to revive, requiring a higher dosage of naloxone. Last year, Dayton allocated $350,000 to accommodate that need.

The city also obtained a federal grant for a pilot program that distributes fentanyl test strips. The idea is to allow users to check street drugs for the presence of fentanyl and its various derivatives. Only a handful of cities have sanctioned the test strips so far.

The city also obtained a federal grant for a pilot program that distributes fentanyl test strips. The idea is to allow users to check street drugs for the presence of fentanyl and its various derivatives. Only a handful of cities have sanctioned the test strips so far.

But Ohio has been dubbed “ground zero” for illicit fentanyl use, and desperate times call for desperate measures.

Which is why Dayton Police Chief Biehl is prepared to do whatever it takes to stem the tide of death that’s plagued his city for too long.

“If it’s about conserving and protecting life,” Chief Biehl says, “it has to be considered as an option.”

For now, it’s an approach that appears to be working.

Sources: